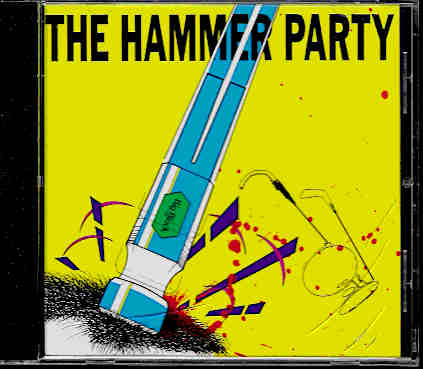

Big Black

12/22/25

Precious Thing

The nerdiest guys you'll ever meet beat the shit out of you with walls of sound. And frankly, I think it's time to talk about it.

Big Black was a Chicago noise rock band founded in the early 1980s by Steve Albini, a person who was hated or respected for most of his career. Coming from Missoula, Montana, Albini moved to Evanston, Illinois for university. As it happened, he eventually became immersed in the Chicago punk scene, populated by bands like Naked Raygun, Rites of the Accused, and The Effigies.

In 1982, Steve put out the first proper Big Black release, the Lungs EP. Recorded entirely by himself in his house, this record is more a prototype for what the band would be about: pressurized bass lines, clanky percussion, and most of all, ground-scraping, cement mixer guitars. Venomous, though diluted testimonials of American despair ("I'm a steel worker, I kill what I eat") set the tone.

I find Lungs to be a particularly reductionistic form of college rock to be seen. I'm a fan of that, actually. However, Bulldozer, on the other hand, is one of the band's most fully-realized manifestations. Another EP, Naked Raygun vocalist Jeff Pezzati and Santiago Durango, former guitarist for Naked Raygun, are appended as long-term and full-time members, respectively. Pezzati was to play bass, and Durango, electric guitar. Roland - the drum machine - stayed on, though Pat Byrne of Urge Overkill was brought in for drums as well.

Much of the fat has been trimmed for this release. A dedicated bassist and a more guitarist-like guitarist accent Albini's predominantly phonetic playing. Especially do I find that more guitarist-like guitarist, Santiago Durango, to be much of why the band could gel. It's like adding a bit of water to a sauce about to burn, the wok smoking like a brick of fireworks on-stage, onions curling at that critical point between "too firm" or "too soft." That must be the value of a real rhythm guitarist: good stir-fry.

Fluidity is a good way to capture this era of the band: still raucous, though with a sense of harmonic interplay (no less a sense of harmony), grinding faster with more intention and will. And then there's the lyrical element, which has also received an overhaul. A lot of Bulldozer focuses on Albini's adolescence and overall life experience in the sticks. Imagery of redneck teenagers killing slaughter cows out of boredom, Indiana towns that kill birds with poisoned corn, and a dog trained to attack black people are all delivered with a "believe it or not" cadence. Our vocalist not only sounds more confident here, but also found a thematic niche that is still reasonably uncharted.

Next is the Racer-X EP, named after the character from the Speed Racer cartoon/anime. The character is referenced here to describe a race-car driver addicted to amphetamines, hence "He's just a regular guy / Racer X got a need / Come on Pops / I need a little more speed." More of the same characteristics with the prior release apply here, minus Pat Byrne. Though, the lack of a live drum overlay does not dampen the experience. Overall, it's more speed and the kind of noises you'd hear in your dad's garage, not to mention culture rot. It's great, and there's also a James Brown cover to top it all off.

Thus ends the Jeff Pezzati phase of the band, at least. Hereon, Dave Riley was brought in for bass duties. Tonally, I don't know that I could imagine a better fit. Riley added a much more direct funk influence to a band that was already kinda funky. This seems tangentially related to his engineering experience for Parliament/Funkadelic.

The result of this new pairing is Atomizer, a god-honest LP. I indicated earlier that the previous two EPs were the band at full force, and I still stand by that, insofar that the force is angled a bit differently here. Would it be fair to call this album-oriented rock? That has nothing to do with the tonal character of the music. The sound at this point is a tight crossover of spastic punk-funk and merciless tectonic insistence. That this is delivered in a full nine-song (plus a live track) record is delicious.

You might've picked up how important middle-American industrial decay is to this band's overall concept. "Kerosene" declares this idea like a mission statement:

I was born in this town

Live here my whole life

Probably come to die in this town

Live here my whole life

Never anything to do in this town

Live here my whole life

Never anything to do in this town

Live here my whole life

Probably learn to die in this town

Live here my whole life

Nothing to do, sit around at home

Sit around at home, stare at the walls

Stare at each other and wait till we die

Stare at each other and wait till we die

Probably come to die in this town

Live here my whole life

You get the idea, surely. Regardless, I find Atomizer's strength to be a lot of its stylistic expansion. For example, "Jordan, Minnesota" uses the band's known belligerence for off-putting tone poetry about a (debunked) pedophilia ring. Meanwhile, "Bad Houses" reflects latent post-punk tendencies, fuzzily recalling an education in Sisters of Mercy or Wire. And of course, "Kerosene" is a seven-minute-long ballad about being so fucking bored out of your skull that you self-immolate. It's not that these tendencies didn't exist previously, but that they seem more obvious and actionable here. This is a noise rock album, for chrissakes.

And then they did it again, for the last time. Songs About Fucking has a couple songs that do in fact mention fucking. If you've witnessed any online presentation of the band, you probably recognize "Bad Penny" as their most famous song, with exception to "Kerosene." This was the track I first heard, and it certainly sets a template. Here is angsty dance-punk with actual fervor and wrath, something you can flail to while spiting your parents. "I think I fucked your girlfriend once / Or maybe twice, I don't remember / Then I fucked all your friends' girlfriends / Now they hate you," Albini says.

Where I said Atomizer is more stylistically diverse, Songs About Fucking feels like a final reassertion of mastery over their techniques. Tracks like "L. Dopa" and "Precious Thing" exhibit interplay between Albini and Durango at peak sadomasochism. Meanwhile, Riley scrawls creases into the center with a soldering iron. Guided by the invaluable Roland - regardless of what drum machine it actually was - The band approaches like fighting to the death, knowing time isn't long no matter what. So, they rock until the establishment collapses, even if they're going with.

Albini wrote in a column sometime in the mid-'80s: "I want to push myself, the music, the audience and everything involved as close to the precipice as possible. Although I'm kinda worried about what we'll find there. All the coolest pioneers of this noise spirit seem to have made the trip to the extreme, been unable, or unwilling, to push on, and tossed in the towel."

He wrote other stuff in that piece which doesn't advertise him very well, but significantly is this the philosophy which I feel guided the band's end - besides important logistical issues. For example, Dave had a drinking problem, and destroyed the drum machine one time. Also, all of them had full-time jobs, and Santiago was going to become a lawyer (which he did, for some reason). They put out the dustier Headache EP that same year, though all-told, that is the general story of Big Black.

But stay for a moment, if you will. Headache may be stripped down compared to previous releases, but there are still some really great moments, including one of my favorite songs by them, the opening "My Disco." Beyond that, if you ever find yourself having reached the end of their recorded output - up to this point, including their handful of singles and live album Pig Pile* (*required reading) - Santiago released two EPs a couple years later as Arsenal. These are also pretty good, if not quite the same.

And some of you might know Steve Albini as a recording engineer. I won't state his obvious credits; anyone can find these easily enough on their own. Nonetheless, I attribute a lot of my personal musical exodus as having initiated through Albini. He was my in for Jesus Lizard, Zeni Geva, Craw, Dazzling Killmen, Uzeda, Engine Kid, Melt Banana, Space Streakings, and so on. If you still like the sound of your dad's garage, culture rot, and tonal juxtapositions, see yourself on your way. The adventure is waiting.

So, that was Big Black: a band that had the nerve to say "fuck you" both to society and the standards of their regional punk scene. Because Big Black was not popular in Chicago and didn't like playing there either, their scorn seems to be indebted to Albini being kind of an asshole, but also very observant of bullshit. I doubt arrogant, self-entitled punk guys were privy to this (which, Albini kinda was himself, but I digress). Either way, I think Big Black's biggest backhand was to play music that was simultaneously more danceable and more violent than - in my humble opinion - really anything their peers were doing at the time.

At least, this is to the extent that they were on the same level as groups like Scratch Acid, No Trend, Laughing Hyenas, (early) Swans, (early) Butthole Surfers, Teenage Jesus & the Jerks, DNA, and so on. And if that's not an invitation to check these band out, I don't know what is. Your homework assignment should be clear by now.