Midori

06/30/25

I cannot in good faith recommend this movie to most people. This is a lurid, rare kind of barbarism. The visual presentation can be crude, and the subject matter explored - and the means by which it is - is socially uneasy at least. However, Chika Gentou Gekiga: Shoujo Tsubaki nonetheless remains one of my favorite films of all time. There will be slight spoilers ahead (nothing major), so if you wish to go in blind, turn back now.

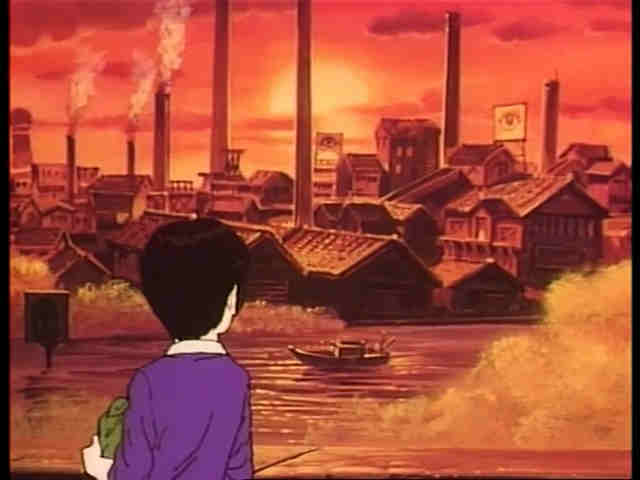

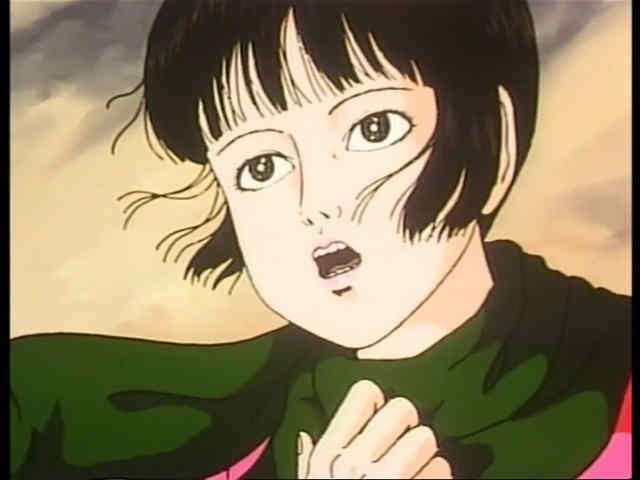

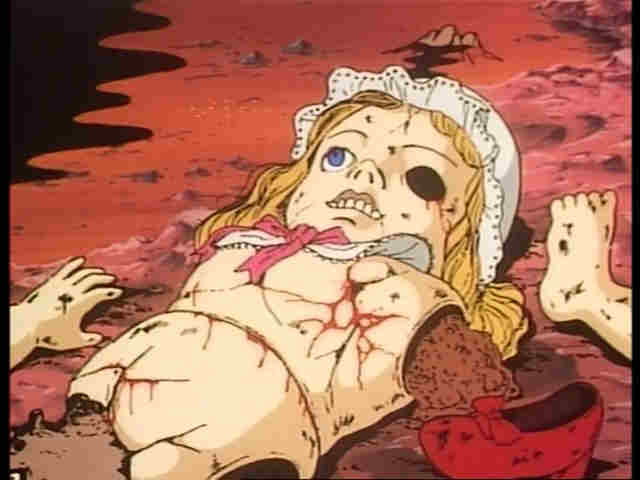

For the unfamiliar, Midori (the film is known as in the west) is a Japanese OVA released in the early 1990s, adapted from the manga by Suehiro Maruo (which I also recommend). Set in the 1920s, the protagonist for which the film is named after is an adolescent girl who joins a traveling freak show after suffering tragedy. She is then to face perpetual abuse and exploitation by the performers.

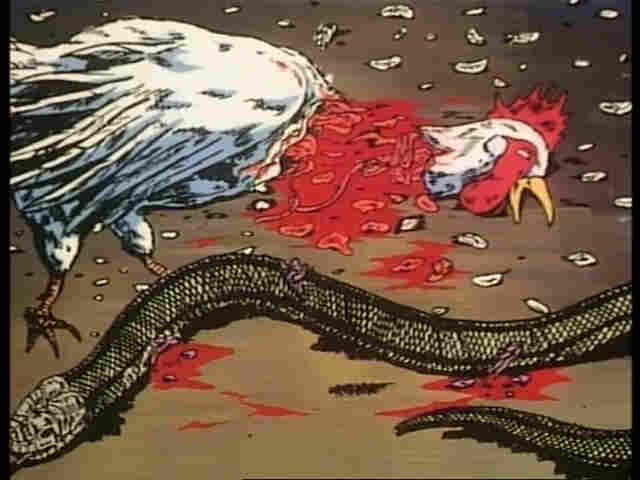

The film candidly exhibits graphic violence and sexual assault, even incorporating some body horror. A lot of this cruelty is aimed specifically at Midori, a character who has few accessible means of escape or retaliation. What distinguishes this depiction of sexual abuse from many others in Japanese media, I find, is that it is not meant as pornographic. Here, bodily coercion is not presented as something the audience should derive pleasure from. Instead, it is expressed in its context of horror and savagery, that which is undeserved, especially as it is aimed at a figure who has done nothing wrong. Such appears to be the mettle of ero guro, or at least Maruo's approach to it: to use pure, human nakedness as a foil to savagery, plague and filth, the entities engaging with each other seemingly towards entropy, extermination, and/or eternal dysfunction.

I believe this depiction and the sentiment it conveys is important. This is because of Midori's willingness to converse unapologetically with the kind of dismal that does not improve, rather stagnating until unsustainable, and dying unceremoniously. I also feel that Maruo's implicit mettle in writing something this hostile is sociocultural. Focusing on it as a period piece, Midori takes place during the latter decades of Imperial Japanese reign, and for obvious reasons, many conceptual entities in the narrative are contingent on this reality. Poverty, social defection, structural fragility and misogynistic violence are all pulled from historical reality into the story. And specifically, I can't help but feel that the latter occurrence - misogynistic violence - is something Maruo wanted to indirectly address in a contemporary position: being a woman or girl in society necessitated to rely on bad men for survival. Knowing what little I know, the gendered situation in Japan is still similarly stiffling.

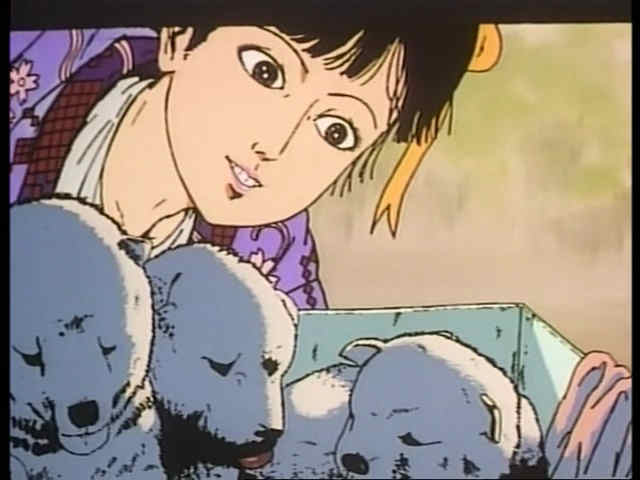

Moreover, visual storytelling greatly facilitates thematic objectives. Fundamental acts of desecration are exhibited alongside lush moments, the characteristically minimal animation (all hand-drawn by one person) being greatly alleviated by so many of the film's images being gorgeous, I find. In that way, the imagery is as antagonistic as the plot is, destabilizing bond security and overall grounding. Maruo's art-style itself is really cool in an interdisciplinary way. As a modern manga, Midori is significantly affected by techniques from Ukiyo-e print-makers like Tsukiyoka Yoshitoshi, famous for his violent samurai prints.

And I mean, there's just generally a vibe, right? There's a special experience in finding this movie on Internet Archive, downloading it, burning it on a DVD, and watching it in a dark basement all by yourself. That's exactly what I did, at least. There's certainly lots of commentary also to be made about a more subversive means of entertainment consumption that a film like this is associated with. Midori has no mainstream or "official" distribution in the modern day, dealing heavy-handed in subjects as bleak as it does, and thus being relegated to niche circles on the digital fringe.

This is not pop culture: you can't sell it, eat it, and it doesn't wanna fuck anyone for money. Rather, I believe its main goal is to have a challenging conversation about abandonment, betrayal and displacement. I feel this discourse has applications to real experiences, and I also find that it is rejected by many safer forms of entertainment. In that way, Midori's unflinching intimacy with its content is a lot of what shocks and charms me about it. Popular culture has its limits in that area of discussion; after all, finding comfort in brutality is uniquely conditioned. Nonetheless, Midori matters to me for being elusive, subterranean, and crudely gorgeous in ways more felt than verbalized.